Welcome to Central Oregon, where the economic news is grim and the bottom is nowhere in sight.

Welcome to Central Oregon, where the economic news is grim and the bottom is nowhere in sight.

THE CENTRAL QUESTION

What will replace Central Oregon’s collapsed housing-reliant economy? The answer is multifaceted — and hopeful.

BY ABRAHAM HYATT

Assembly specialist Jonny Carrick at work at PV Powered. The company is part of the diversity of businesses that will help the region regain its economic footing. Assembly specialist Jonny Carrick at work at PV Powered. The company is part of the diversity of businesses that will help the region regain its economic footing.PHOTOS BY JOSEPH EASTBURN |

Welcome to Central Oregon, where the economic news is grim and the bottom is nowhere in sight. It’s no secret why: The one major engine behind the region’s fast-paced growth was the housing boom. When that evaporated, the reverberations slammed through the region, hitting some of the biggest employers, like wood products manufacturing, particularly hard.

Between November 2007 and the same month in 2008, Deschutes County lost 6.2% of its construction-industry jobs, and 6.1% of its manufacturing jobs. By last fall, the indicators that economists use to measure the health of an economy became very bleak.

In November, unemployment hit an 18-year high, with the Bend area posting a jobless rate of 9.9% — up from 5.4% the year before. Between the final quarter of 2007 and the third quarter of 2008, passenger activity at the Redmond airport was down 5%, and help-wanted ads in the Bend Bulletin were down 64%, according to research by University of Oregon economist Tim Duy.

Not surprising, building permits, while up from the second quarter, were down 56% from the previous year. A report released in December by the state’s office of economic analysis further emphasized how dependent the Central Oregon labor force was on the growing housing industry.

In 2007, employment grew at a rate of 1.7%. But between the third quarter of that year and 2008, it dramatically reversed course and dropped .4%. At the same time, business bankruptcies statewide jumped 22%.

What will save Central Oregon? Economists and those involved with economic development agree that there won’t be a specific engine that drives growth in the region again; real estate will never again play the role it once did. But what will replace it?

The answer comes in the form of a list. What will save Central Oregon, say those in the region, will be a tapestry of industries and the big and little companies that comprise them: high tech, aviation, green tech, niche manufacturing, bioscience, health care, tourism. Some of these, like high tech, are strong despite the recession.

There’s room in the region for these companies to grow. Redmond, for instance, aggressively kept up with the demand for industrial land over the last few years and now finds itself in a position where it can meet the needs of local companies who are currently expanding.

Shovel-ready land, however, isn’t available in all cities. Bend will struggle to provide manufacturing-ready property for the next few years until it’s able to expand its growth boundary. The city is also grappling with transportation infrastructure issues at Juniper Ridge, currently its only major industrial-ready site.

A portrait of what companies, either local or newcomer, will fill those commercial properties in Redmond or Bend or any other city is unknown. The most educated guess is that it will be a broad range. It may be tempting to try and predict which industries will be the next hot up-and-comer, Duy says, but Central Oregon’s recovery will most likely be predicated on a much more nuanced picture.

Vice presidents Erick Petersen (left) and Steve Hummel at PV Powered, a Bend tech company that’s expanding. Vice presidents Erick Petersen (left) and Steve Hummel at PV Powered, a Bend tech company that’s expanding. |

“There’s no natural grouping of industries that will propel [a rebound],” he says. “We become too tied up in what specific industries are going to lead us out. What’s more likely is that we’ll bottom out and then our general growth over time will lead us out.”

As part of that general growth that Duy describes, some industry sectors will grow faster than others. The high-tech cluster, with its collection of approximately 60 hardware, software and biotech companies, is often used as an example. Growth in the cluster over the last five years has been strong, with several companies expanding their workforce and several of the largest companies — Advanced Power Technology and Accent Optical Technologies — being purchased by firms outside of Oregon.

There are risks inherent in developing a tech industry sector in a relatively remote place like Deschutes County. “Central Oregon’s high-tech industry has always reflected larger national trends. As the competition for talent increases in the Bay Area, Seattle, and Portland, Central Oregon gets a chance to play a larger role. When those areas decline, the first place investors and employers cut is out-of-the-way places like Bend,” says Bill Moseley, CEO of Bend-based GL Suite.

Moseley’s company makes software for government regulatory and licensing agencies. By the end of 2009, it will have expanded into a new facility and increased its staff by 20 workers. It’s that kind of mid-recession growth that people like Roger Lee, CEO of the Economic Development of Central Oregon (EDCO), Doris Penwell, head of economic development for the Association of Oregon Counties, and Clark Jackson, a business development officer with the state’s Economic and Community Development Department, point to when they talk about the role high tech will play in shaping the region.

| CURRENT EMPLOYMENT TOTAL NONFARM PAYROLL EMPLOYMENT |

| OREGON Nov. 2007: 1,755,600 Nov. 2008: 1,721,600 BEND MSA (DESCHUTES COUNTY) CROOK COUNTY JEFFERSON COUNTY SOURCE: Oregon Employment Dept. |

“They’re going to be small drivers, not like what you see over here in the [Willamette] Valley,” Penwell says. “But these are firms that are still going to be growing from 50 to 150 employees.”

PV Powered is another Bend-based tech company that’s in the middle of expanding. The company, which makes solar-power systems, has moved to a new location in Bend and plans on adding up to 200 more employees by the end of this year.

“I have to be careful saying this, but frankly, I hope [Central Oregon] doesn’t return to such a one-sided economy that’s dominated by real estate,” says Erick Petersen, VP of sales and marketing. “We’re tech guys. We think diversifying the economy around tech creates much better living-wage jobs.”

Manufacturing will also play a key role in the larger growth pattern in Central Oregon. The label “manufacturing” encompasses a broad spectrum, everything from niche industries, to the aircraft cluster, to wood product companies, which still employ one out of every three workers in the manufacturing sector, despite taking major hits over the last year.

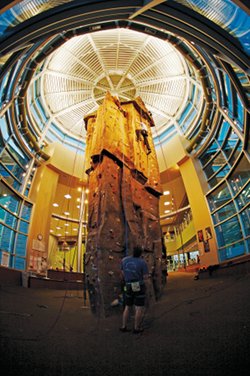

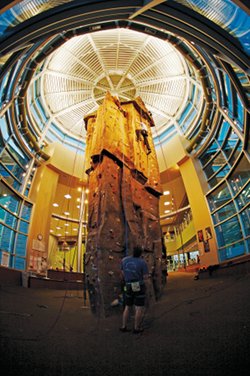

Within the various niche industries, the sporting goods mini cluster — like the high-tech sector — is often mentioned as having a growing role. Jennifer Woods, a senior international trade specialist with the U.S. Commercial Service, lists some of the fastest growing: Metolius Mountain Products (rock climbing equipment), Ruff Wear (outdoor gear for dogs), Greatoutdoors.com (online retail), Kialoa Canoe Paddles, and Entre Prises (climbing walls and handholds). Many of them, she says, are finding work on the international market to balance out what’s happening at home.

At Entre Prises, international- and national-level work has kept the company from feeling, for the most part, the regional economic crash, says marketing and sales VP Adam Koberna. While Entre Prises may focus on the world outside Central Oregon, it — along with the rest of the manufacturing sector — has a very local concern: a stable workforce. In recent years, the booming construction industry created a shortage of workers in manufacturing.

“In a strange way this [economic situation] has been a benefit for us when it comes to people to hire,” Koberna says. “Now that the worker pool is deeper, we’re able to find quality people. If things pick back up, that’s going to be one of the biggest things we’re concerned about.”

Entre Prises in Bend has built climbing walls, like this one at the YMCA of Greater Wichita, for hundreds of clients. PHOTO COURTESY OF ENTRE PRISES |

Economic growth is only possible if there’s a place for businesses to grow or move into. Over the past several years, Redmond has aggressively expanded its urban growth boundary, which has allowed it to respond to the need for manufacturing-ready land far quicker than its neighbors, Jackson says. That expansion process is crucial for cities, he says, because the enterprise zones that are subsequently created are one of the only tools a city has in attracting and keeping businesses. Prineville and Madras are following in the footsteps of Redmond.

Bend, on the other hand, started the expansion process much later. After a year and a half of planning, the city council in January approved a plan that would expand the growth boundary by 8,464 acres.

But that plan still must be approved by county and state agencies. City manager Eric King says that because of the city’s slow progress, officials will remain focused on the ongoing planning process, not business recruitment, in the next few years.

“When a business wants to locate here, you can’t say, “Hey, wait a year while we fix these issues,” he says. While it’s obvious the lack of shovel-ready manufacturing sites will have some kind of an economic impact on Bend, it’s unknown what it means to the region. Land is cheaper and the cost of living is lower in Redmond and other small cities, so companies may choose to locate there regardless of Bend’s ability to expand its boundaries.

Despite public agencies’ efforts to stimulate growth, the overall economic market sometimes dictates success or failure. The best example of why Central Oregon’s economy will be rebuilt by many different industries instead of one major player lies in the aircraft cluster. The sector was once considered an economic rock star, providing thousands of jobs that ranged from manufacturing planes to making safety and utility equipment for helicopters and airplanes.

But the past two years saw massive job cuts and a slowdown in the high-end aircraft industry, with layoffs at Epic and Cessna. The aircraft cluster will come back, says EDCO’s Lee: “There are still companies doing commercial work in general aviation. That’s going to be the strength.”

When the cluster does come back, however, it won’t be as a replacement for the fallen housing industry. Neither will the high-tech or manufacturing industries by themselves. And that, says Duy, is a good thing.

“I’ve always been wary of over-emphasizing one sector’s importance. In my experience, wide growth is generated by relatively bland industries,” he says. “We look for the sexy industries. We write stories about them. But in reality it’s much more simple.”

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]